Coaches Need to Prioritize Access to Knowledge

I’ve heard many coaches say some version of this:

“I don’t understand it. We’ve worked so hard, we have great scrim results, then we walk on stage and it’s like their brains turn off.”

Why does this happen?

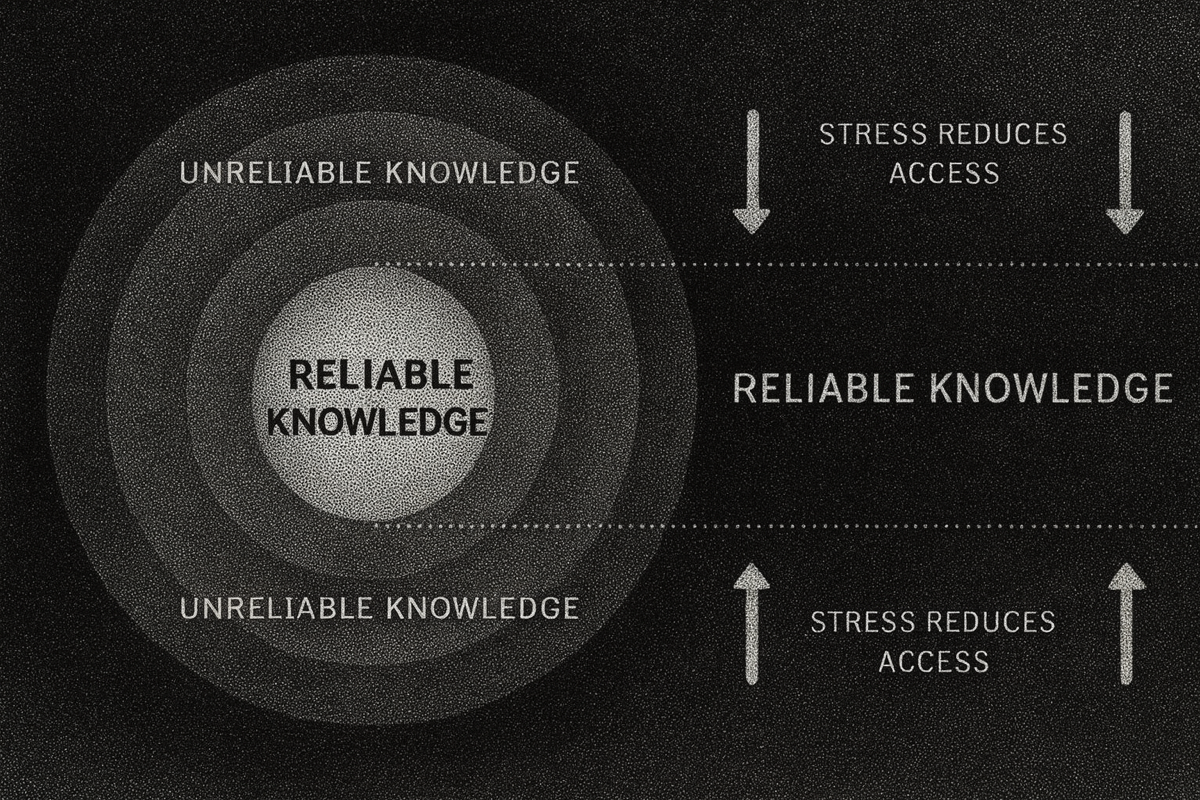

Most coaches believe they’ve taught the right things. And probably they have. But when pressure rises, players can’t execute those things. The issue isn’t always the content of the coaching, it’s the player’s access to that knowledge when it matters.

When stress is high, access to knowledge drops. It becomes a bottleneck that nerfs performance.

This is especially true when the learning process was rushed, poorly structured, or disconnected from team identity.

So, how can we make sure players can actually use what they know under stress?

Understanding Knowledge

Knowledge is what lets you recognize patterns, connect ideas, and turn information into action. But it exists in layers and not all of them are equal under pressure.

You can think of knowledge moving through five phases:

Stored – You’ve learned it, but you need cues or time to recall it.

Accessible – You can recall it when prompted or focused.

Operational – You can use it deliberately and explain your reasoning.

Fluid – You use it effortlessly and consistently.

Embodied – You are the knowledge. You operate from it without thinking.

The goal is embodiment. The deeper the knowledge is integrated, the less it depends on conscious recall. And the less stress can disrupt it.

Understanding Stress

Stress is the body and mind going into high gear when demands exceed capacity.

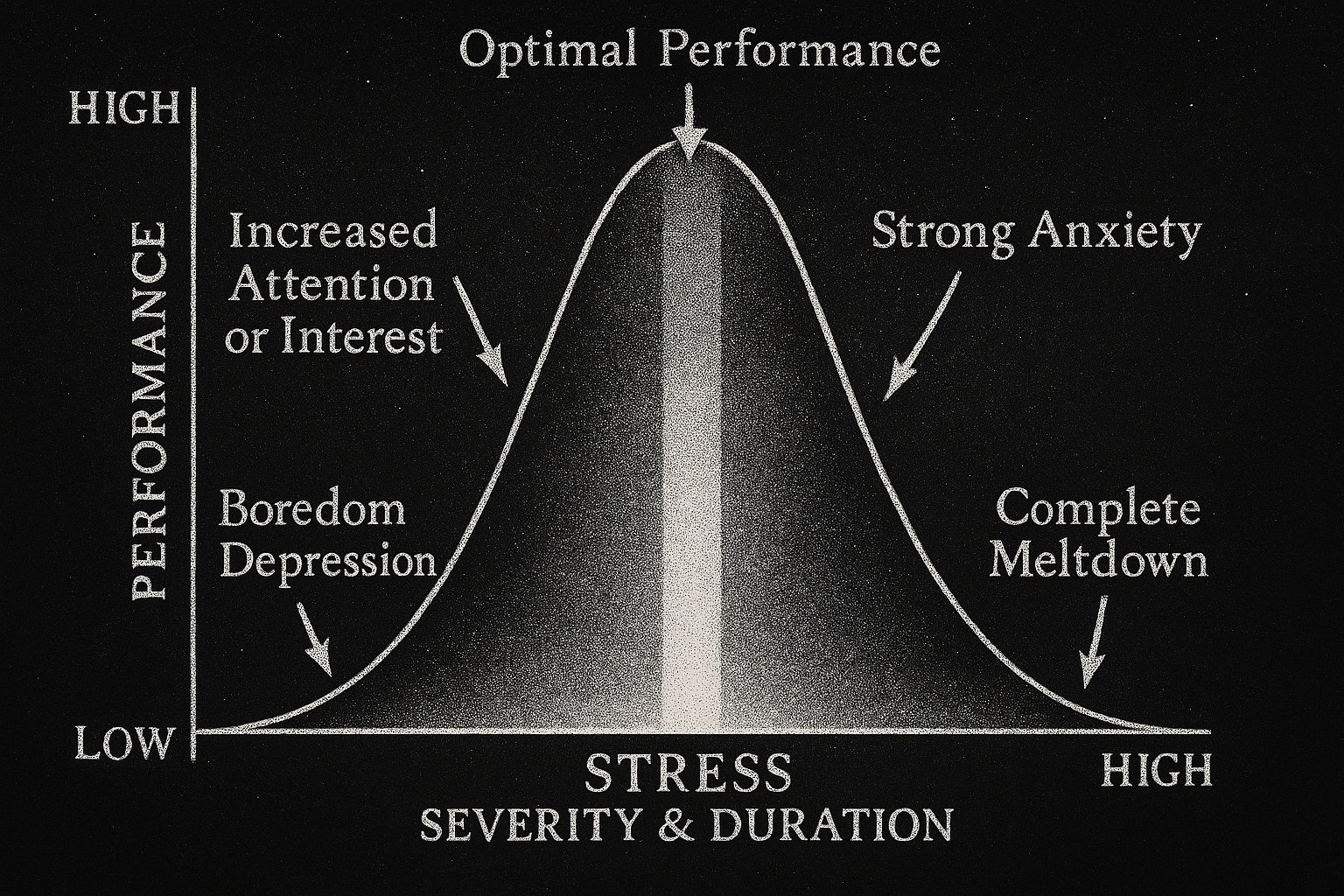

It’s not inherently bad. In fact, the right amount of stress helps us perform. But too much or too little quickly becomes a problem.

When stress gets too high, your focus tightens, memory slips, and decisions start dragging. When it’s too low, your mind wanders and motivation fades.

I’ve seen both extremes.

Back when I was a professional poker player, I’d played 24 tables at once. That was my sweet spot, just enough pressure to keep my mind sharp. But if I dropped below 16 tables, things went downhill fast. I started getting bored and overanalyzing every hand. My focus slipped, and so did my performance.

Pro players and teams experience the same thing in their own way. When the challenge is too low, like scrimming a team far below their level, the mind drifts. The game stops demanding their full attention, they start taking unnecesary risks and the game becames “a clown fiesta”.

You can see this when LEC or VCT teams scrim their academy rosters. The main team often plays loose or careless because it feels too easy. The academy players, on the other hand, come in full of energy and hunger, ready to prove they belong.

That imbalance can be frustrating, but smart coaches use it as a training opportunity. These sessions become focus and discipline work. The goal is not to crush the opponent, but to play clean, master the fundamentals, and raise the floor of performance.

Types of Stressors

Not all stress feels the same, and it doesn’t always come from where you expect.

Here are some of the most common ones and how they impact performance:

| Domain | Core Interference | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | Info overload, tunnel vision, fatigue | Missing or misusing information |

| Emotional | Anxiety, tilt, frustration, shame | Your focus slips and recall slows down |

| Physiological | Lack of sleep, poor nutrition | The brain just runs slower |

| Social | Lack of trust, unclear roles, team noise | Communication breaks down and info gets lost |

| Systemic | Bad tools, inconsistent language, messy routines | Fragmented shared knowledge |

Some stressors are internal, others external but they all narrow your focus and make it harder to use what you already know.

How Stress Affects Access to Knowledge

When stress spikes, access to knowledge doesn’t vanish, but it becomes unreliable.

You might “know” something, yet still fail to use it when it counts.

Here’s how stress interacts with each stage of knowledge:

Stored: You’ve learned it, but can’t reach it fast enough. Under stress, it stays locked away, the classic “my mind went blank” moment.

Accessible: You can recall it when calm, but stress slows recall. You realize what you should’ve done right after the play.

Operational: You can use it deliberately, but under pressure you start overthinking and lose flow.

Fluid: You perform naturally, but if arousal spikes too high, execution can get rigid or rushed.

Embodied: Knowledge and action are one. Stress actually sharpens focus here. This is the clutch zone.

Maintaining Access to Knowledge

Once you see how stress affects recall, three key coaching priorities start to stand out:

Integrate knowledge deeply.

Expand tolerance to stress.

Build stress reset systems.

Let’s go through each.

1. Integrate Knowledge into the Subconscious

The deeper the learning goes, the more stable it becomes under stress.

Chunking and scaffolding: Break complex ideas into smaller pieces and build them layer by layer. This lightens mental load and speeds up recall.

Shared language: Use consistent terms so players don’t waste time translating ideas mid-game.

Reflection and debriefing: Reviewing what happened and why helps transform short-term insights into long-term understanding.

The more connected a player’s mental map is, the easier it is to navigate under pressure.

2. Increase Tolerance to Stress

Warmups and pregame routines: Create reliable rituals that regulate arousal and set a calm, focused tone.

Volume training: High-frequency reps under realistic conditions make pressure feel familiar.

Simulated matches: Practice under stage-like settings (lights, noise, cameras, jerseys, 5 minute pause between games) until it feels normal.

Over time, stress shifts from threat to fuel.

3. Implement Stress Resets

Even well-trained systems need recovery.

Hard resets: Sleep, rest days, and structured cooldowns restore full capacity.

Emotional resets: “Empty the backpack” seesions, “flame meetings” or honest team talks help release frustration before it piles up.

Soft resets: Short breathing pauses or “what’s next” calls help players refocus in-game.

Rest, reflection, and regulation protect a player’s access to what they already know.

Overlaps and Synergies

These methods naturally reinforce each other.

Reflection loops both integrate knowledge and release tension.

Volume training builds both skill and stress tolerance.

Shared language improves communication and recall speed.

Each layer strengthens the next, keeping access stable when pressure peaks.

A Deeper Look at Chunking and Scaffolding

Over the years, I’ve seen many coaches rely on the same teaching routine again and again. I call it the conference–practice cycle.

The coach runs a theory session, explains a concept, and maybe shows a few examples of pro teams executing it.

The team goes into scrims. Some games go well, others don’t.

Post-game review time. The coach explains what went wrong, or asks players to figure out the right play themselves.

Then the process repeats until the team finally executes the concept correctly.

Does it work? Yes. Is it optimal? Not really.

It takes too long to teach, and the knowledge often doesn’t stick because this approach rarely uses chunking or scaffolding, two of the most effective tools for helping players retain and access what they know under pressure.

When stress narrows attention, only well-chunked knowledge survives.

Chunking creates ready-made action units that the brain can recall instantly. Under stress, you can’t compute an entire play, but you can execute a chunk that feels automatic.

Scaffolding ensures those chunks are built correctly. It means layering difficulty gradually so each step prepares the next.

If you skip too far ahead players form fragile chunks that fall apart under stress.

When scaffolding is done properly, the patterns that form are stable, adaptable, and transferable across situations.

Many coaches avoid chunking and scaffolding because they worry players will only learn specific tactics instead of learning to think.

But the opposite is true. Chunking and scaffolding build the foundation for real understanding.

Coaches often see the game as an intellectual puzzle to solve.

Players experience it differently. For them, it’s also physical and emotional. Connecting the cognitive to the experiential is what allows deep learning to happen.

By simplifying the cognitive side first, then letting players experience the theory in action, you create the base for everything that follows: advanced concepts, complex executions, and the ability to make micro-adaptations under pressure.

Final Thoughts

Knowledge is essential, but without access, it’s useless.

Creating the right conditions for access, especially under stress, is one of the most important parts of coaching.

The key takeaway is simple: a coach’s job isn’t to teach more knowledge faster. It’s to teach better.

Teach in a way that helps players use what they know when it matters most, not just in scrims, but on stage.

That’s the real art of coaching.