The Myth of Autopilot in Esports

In esports, “autopilot” is usually a bad word.

When a player keeps making the same mistakes, misses obvious context, or doesn’t adapt, you hear it coaches say:

He is on autopilot.

He is not thinking.

His has turned his brain off.

And honestly, I get why people say that. From the outside, bad execution can look lazy or disconnected. It feels like the player isn’t really there.

But after close to two decades working with professional players in real competitive environments, I’ve come to see autopilot very differently. Not as something to avoid, but as something you actually need. And not as the problem itself, but as the place where the real problem shows up.

The question isn’t whether players should play on autopilot. They always will. The real question is what kind of autopilot they’re running.

What People Usually Mean by “Autopilot”

Most of the time, when people say “autopilot,” what they really mean is “not thinking.”

It usually comes up after a familiar set of things happens. A player keeps making the same mistake even though it’s already been pointed out. They don’t adjust when the situation clearly changes. They walk into the same bad fight, take the same risky path, or default to the same option no matter what’s going on around them.

From the outside, it feels like the player is stuck on rails.

There’s also a strong emotional side to this. When execution drops, coaches and teammates want to see effort. They want to feel like the player is engaged, fighting the situation, trying to solve the problem in real time.

So when the play looks automatic, it can feel flat. Like the player is just going through the motions instead of really being there. It’s easy to read that as someone mentally checking out or not paying attention.

From there, the conclusion almost writes itself. If the problem is that the player isn’t thinking enough, then the solution must be more focus, more awareness, or more conscious control during the game.

The issue is that this isn’t actually what’s happening, so the conclusion is wrong.

In most of these moments, the player is thinking, just not consciously in the moment. They’re running the patterns that feel safest and most familiar under pressure.

That execution looks automatic because it is. But automatic doesn’t mean careless or lazy. It just means control has shifted away from deliberate thinking and toward learned responses.

This distinction matters. If we treat autopilot as a sign that the player isn’t trying or doesn’t care, the response is usually pressure and demands for more effort. If we see it as automatic execution of a limited or uncomplete model, the response changes. It becomes about learning, depth, and better preparation, not about forcing more thinking into the game.

What Autopilot Actually Is

At a basic level, autopilot is what happens when actions are controlled by patterns that have been learned well enough to run without conscious thought.

The brain recognizes a situation, matches it to something it has seen before, and responds automatically. There’s no internal debate, no step-by-step reasoning, and no running commentary in your head. Things just happen.

That doesn’t mean the player isn’t aware of what’s going on. They’re still seeing the map, hearing comms, reading movement, and reacting to changes. What’s missing is the feeling of actively deciding every action. Control has shifted from conscious reasoning to learned responses.

This shift is how the brain is designed to work under speed and pressure.

Games move too fast for constant conscious control. If every movement, ability, or rotation had to be reasoned through in real time, performance would collapse almost immediately. Autopilot is what allows players to act quickly, smoothly, and consistently without burning all of their mental energy on basics.

Another important point is that autopilot doesn’t choose what to do. It executes what’s already there. It runs the patterns that have been practiced, reinforced, and made familiar. If those patterns are solid and well-aligned with the game, execution looks clean and confident. If they’re shallow or outdated, execution looks repetitive and wrong.

That’s why autopilot itself isn’t good or bad. It’s neutral. It’s a delivery system.

Think of it like muscle memory, but broader. It’s not just mechanics. It includes how a player positions, how they prioritize information, how they react to pressure, and how they default when things get chaotic. All of that can become automated.

This also explains why autopilot often feels calm from the inside, even when things are going poorly. The player isn’t panicking. They’re doing what feels normal and reasonable to them. From their perspective, the decisions make sense. From the outside, it can look confusing or stubborn.

Autopilot is also not something players consciously switch on or off. Under pressure, it takes over naturally. As speed increases and stress rises, the brain relies more on what’s already been learned and less on slow, effortful reasoning.

It’s also why telling players to “stay out of autopilot” usually doesn’t work. In the moment, they don’t have access to a different control system. The only thing they can execute reliably is what has already been internalized.

Where conscious thinking does matter is before and after the game. That’s where patterns are shaped, refined, and reinforced. That’s where players build the autopilot they’ll rely on later.

So when we talk about autopilot, we’re not talking about a lack of thinking. We’re talking about thinking that already happened, showing up automatically. The quality of play depends on the quality of that earlier work.

Understanding autopilot this way changes the conversation. Instead of trying to suppress it, the goal becomes to build it carefully, knowing it will always be there when it matters most.

Autopilot is Needed for Flow

When a player has a great game, we usually hear things like “he was in the zone” or “everything just clicked.” That’s usually how people describe a flow state.

That might sound very different from being on autopilot. In practice, though, autopilot is what makes flow possible. Especially when we’re talking about automatic flow.

Understanding Flow

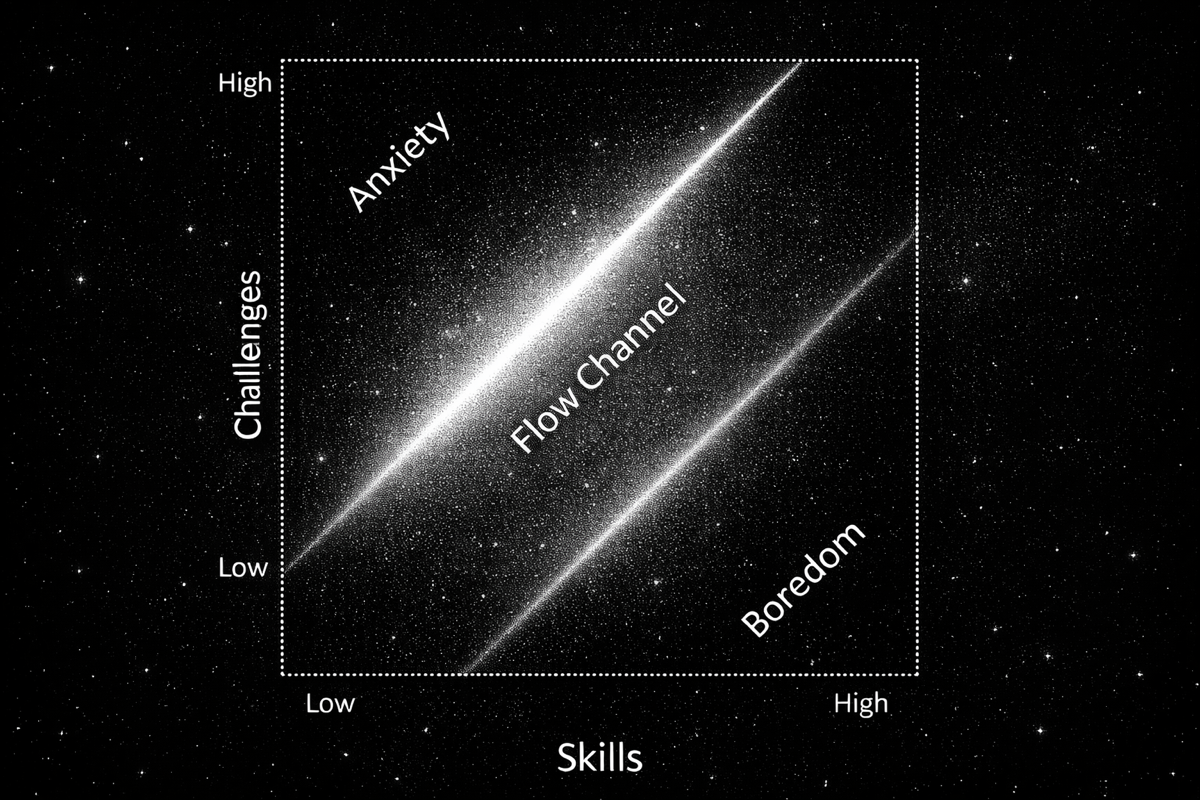

Flow is a performance state where attention is fully locked into the game, decisions and actions feel aligned, and performance happens smoothly without self-interference. Players are fully engaged in what’s happening right now, with no mental noise pulling them away from execution.

There are two core types of flow: deliberate flow and automatic flow.

Deliberate flow is when you’re fully locked in, but you’re still actively thinking. You’re solving problems, adapting, and making decisions on purpose, without overthinking or judging yourself. This usually shows up when you’re learning, adjusting strategy, or dealing with new or unexpected situations.

It’s the ideal state for learning and active problem-solving, like during drills or certain moments in postgame review when you’re really engaged. In actual matches, a shotcaller might spend around 30–40% of the time dipping into this mode in short bursts, while a carry who mostly gives information might be closer to 5–20%.

Automatic flow is when execution dominates. Skills are already learned, trust is high, and actions unfold with little conscious control. Thinking about how to act would actually make performance worse, so control shifts to automatic processes.

Autopilot is needed for automatic flow because:

It lets well-learned skills run without interference.

Automatic flow is about executing things you already know how to do extremely well. Autopilot shifts control away from conscious thinking so those skills can unfold smoothly instead of being slowed down by decision-making.

It enables speed and fluidity.

In automatic flow, situations evolve too fast for step-by-step thinking. Autopilot allows instant pattern recognition and response, which is necessary for actions to feel quick, natural, and precise.

It prevents overthinking and self-monitoring.

When autopilot is active, there’s no room for inner commentary or micromanaging your actions. That absence of mental noise is essential for automatic flow to stay stable and uninterrupted.

If execution isn’t automated, awareness collapses when effort raises. If awareness drops, execution turns into blind repetition.

Flow happens when both layers are doing their job at the same time.

Building a Better Autopilot

If autopilot is always going to take over under pressure, then the real work is making sure it’s worth relying on.

A better autopilot is built by shaping what gets automated and how stable those patterns become. That process mostly happens outside of matches, long before stage pressure shows up.

1. Limit changes

One of the biggest mistakes teams make is changing too many things at once. New concepts, new priorities, new rules, new exceptions. Constant change prevents patterns from settling. Players never get enough repetition in the same structure to let decisions sink in.

Automation needs stability. Not forever, but long enough.

That doesn’t mean mindless repetition. It means repeating the same framework while letting players experience many situations inside it. Over time, they stop solving the basics and start recognizing patterns. Decisions get faster, cleaner, and more consistent without needing conscious effort.

2. Split learning mode from performance mode

Learning is effortful. It’s uncomfortable. It involves stopping, discussing, testing, and sometimes breaking things on purpose. This is where thinking belongs. This is where players should be fully aware of what they’re doing and why.

Performance mode is different. Here, the goal isn’t to explore. It’s to execute. Simplicity matters. Fewer rules. Clear priorities. Trust what’s already been practiced.

Mixing these two modes constantly can slow down progress. If players are always trying to learn new things while playing full-speed games, autopilot never gets a chance to solidify. Execution stays fragile.

Volume also matters, but only when it’s aligned.

Grinding games can help build autopilot, but only if the goals of that volume match what the team actually wants automated. If individual practice pulls players toward habits that conflict with team play, those habits will still show up under pressure. Autopilot doesn’t care where it learned something. It just runs it.

3. Prioritize rest

Autopilot improves when patterns are reinforced and then allowed to settle. Chronic fatigue makes everything shallow. Players fall back on the simplest responses, awareness drops, and bad habits get reinforced instead of corrected. Resting is part of how learning consolidates.

Over time, as more things move into autopilot, players gain something important: mental space. They can notice more. Adapt faster. Handle pressure better.

Building a better autopilot takes patience. It can feel slow, especially compared to constantly adding new ideas. But when it works, execution becomes calmer, more consistent, and more resilient under stress.

And that’s usually what shows up on stage.

Where Thinking Actually Belongs (The Tree Analogy)

One of the biggest challenges in coaching is deciding when players should be thinking, and what they should be thinking about. A useful way to frame this is with a simple tree analogy.

Think of a player’s decision-making like a tree with three levels:

The trunk represents the fundamentals. Core mechanics, role basics, default positioning, standard patterns. These are the things that show up in almost every game, regardless of opponent or situation. They’re the base of everything else.

The main branches are the common decisions that grow out of those fundamentals. Typical macro rotations, standard responses to pressure, communication defaults, usual ways of playing fights or skirmishes. These aren’t identical every game, but they’re familiar enough that players see them all the time.

Then you have smaller branches and the leaves. These are variations, exceptions, and fine adjustments. Small optimizations. Context-specific choices. The details that change from game to game.

All these smaller branches and leaves are connected to a main branch. If you understand deeply the concepts on the main branch, you’ll always be able to adapt when these adaptations or new situations come up.

The key idea is that most in-game execution should live in levels one and two, in the trunk and main branches. Those decisions shouldn’t require active problem-solving during play.

When fundamentals and standard patterns are automated, players can act quickly and smoothly. There’s no hesitation, no internal debate, no mental clutter. The game flows forward instead of feeling heavy.

Thinking, on the other hand, is most valuable at the edges of the tree.

The leaves are where context really matters. These are moments where conscious attention and adaptation actually help. This is where awareness should zoom in and deliberate thinking can add value.

Problems show up if players have to consciously reason through trunk-level decisions in-game, stress goes up fast. Reaction time drops. Mechanics suffer. Communication becomes messy. The brain gets overloaded trying to solve things that should already be solved.

On the other side, if players never think at the leaves, autopilot becomes rigid. They repeat patterns even when the situation clearly calls for something else. This is where awareness matters. Not constant analysis, but enough presence to notice when the environment has changed.

The goal is to place thinking correcty

Most thinking should happen outside the game. During review. During prep. During focused practice. That’s where trunk and branch-level decisions are built and reinforced. That’s where players can slow down, ask questions, and reshape patterns without pressure.

During the game, thinking should be light and selective. Players should mostly be recognizing, not solving. Acting, not debating. Adjusting at the edges when something genuinely new appears.

A simple rule of thumb helps here: if a decision comes up often, it belongs lower on the tree. If it’s rare or highly contextual, it belongs higher up.

When thinking is placed this way, execution feels cleaner. Players don’t feel rushed or overloaded. They have mental space to communicate, read the game, and adapt when it matters.

That’s what the tree model is really about: giving thinking a structure that matches the speed and pressure of competition.

Final Thoughts

Autopilot isn’t the problem in esports. It’s unavoidable, and it’s necessary.

When pressure rises, players don’t suddenly start making careful, step-by-step decisions. They fall back on whatever has been learned well enough to run automatically. That’s not a mindset issue. That’s how the brain works.

So when play looks repetitive or off, it usually doesn’t mean the player “stopped thinking.” It means the autopilot they’re using is limited, outdated, or not aligned with what the game now requires. Autopilot doesn’t cause mistakes. It exposes what’s actually been trained.

That’s why the real work happens before the match. Building strong fundamentals, stabilizing patterns, and deciding what should be automated and what should stay flexible. Thinking belongs in practice, review, and prep. In-game, most decisions should already be solved.

Players will always run on autopilot when it matters most.

The only real question is whether it’s the right one.